TOGETHER

Remains of the Welfare State

Jyvaskyla, FI

The housing towers and blocks that have come to represent the identity of Kortepohja are perhaps perfect examples of the tendencies in late modernist housing. Supported by the institution of the welfare state, housing became a matter not only of architecture, but became a matter of policy. Architects were called upon to play a very specific role in the apparatus of the welfare state, to provide housing in an accessible, efficient and satisfactory way. The dictum “a house is a machine for living in” became the perfect vehicle for the modernist housing agenda, reducing the notion of housing to a limited set of quantifiable metrics. The resulting buildings, with highly efficient layouts and good access to natural light and fresh air, served as an approach to housing that continues to this day. Safeguarded by the social institution of the welfare state, architects were able to focus the concerns of housing on addressing basic human needs and momentarily avoid addressing possibly the most fundamental concern of mass housing, how we live together.

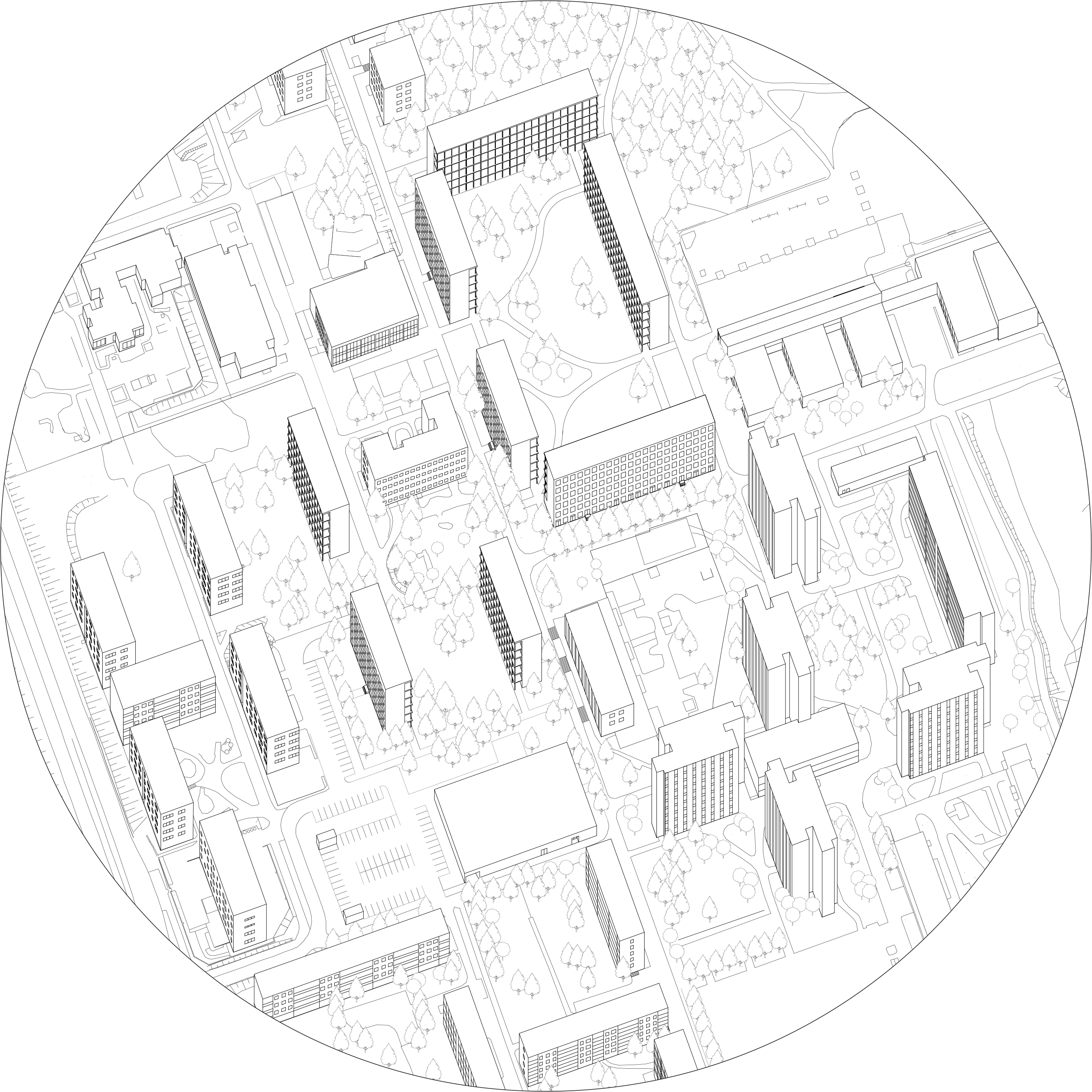

As we consider the future of Kortepohja, we observe that the challenges it faces are the result of the friction between the social ambition of the town plan and the assumptions of housing in architecture. The 1964 scheme by Bengt Lundsten was an explicit critique of the forest-town planning tendency of the time. Championed by figures such as Alvar Aalto and Reima Pietilä, the forest-town’s singleminded focus on sculptural aesthetics and a romantic notion of closeness to nature was criticized by Lundsten’s generation for the lack of social content. With Kortepohja, Lundsten sought to re-introduce a concept of the urban to town planning in Finland by referencing 1800’s Finnish wooden town planning and their coherent grid structures. The dense, yet low strategy aimed to engender social contact through the compact urban environment, common courtyards and regular pedestrian avenues. When the 1970’s housing towers and blocks were introduced in the student housing area, the social environment of Kortepohja was radically altered. Though these newer buildings adhere to the order of the grid plan, the imperatives of density led to a radically different understanding of the role of architecture within the overall town plan. The universal character of these buildings, repeatable, homogenous and with no relationship to the surroundings reflects the late modernist tendency of treating housing as singular architectural objects inserted into green public space. In this sense, the 1970’s housing of Kortepohja bears a greater similarity with suburban development than to any conception of the urban. Approached in this manner, the courtyards and public space formed by the grid structure of Kortepohja became merely representational. Without a means of mediating the hierarchy between the shared realm of the courtyard and the public realm of the street, the sense of community made possible by the shared landscape was lost.

This project proposes to further strengthen the compact, contact approach that has come to define Kortepohja by subtly tweaking the main housing typology of Kortepohja with the introduction of the gallery access housing block. Though the overall geometry of the gallery access block appears similar to the current lamella-type blocks, it has a radically different effect on defining the courtyard spaces within. The gallery access block always defines a direction, and creates the possibility of a public and semi public edge. The accompanying dwelling types, defined by a linear “tunnel-room” creates a clear hierarchy of public to private space and offers the possibility of a shared balcony overlooking the courtyard spaces. The 3m structural bay of the room can be repeated to accommodate various living situations and these different housing types can be arranged throughout the block to respond to various conditions. For example, the two bay family apartment can be used to define a public ground condition with the two storey configuration, or be placed seamlessly with the single apartments to create new sharing conditions on the balcony. This simple, unashamed blunt logic, one bay per individual, regardless of housing type represents in a very direct way, the equal right to housing.

Today, the anonymous, contemplative character of Kortepohja remains its strongest asset and an identity defining characteristic that is surprisingly fitting for a student district. The community atmosphere of Kortepohja does not revolve around lively commercial streetscapes, but in a shared respect and connection with the surrounding landscape. Though this project proposes to remove the understandably iconic MNOP building, the singular iconicity of the MNOP building is replaced with the structuring form of the 6 storey gallery blocks. The character of the blocks does not arise from being the tallest or the flashiest, but in their ability to define and connect with the shared green space. Together, the unassuming blocks stand out as a structuring form that reinforces the grid character of Kortepohja.

In Finland, modern architecture has played a vital role in the construction of the welfare state. The imperative to build cheaply and efficiently while remaining adequate to basic human needs was the necessity of post-war urbanization and rebuilding. Yet the challenges of Kortepohja show us that housing plays a role beyond satisfying these basic needs. With the seeming inevitable retreat of the welfare state in the face of the global acceptance of austerity, it is more important than ever to consider the role of housing in building the social conditions we live in.